I am reading a lot of blogs and papers that people write about their thought processes for the craft their good at. Not all are strictly product management, some are from similar fields. I consume a lot of adventure game content these days, and if you look at game design for adventure games, there’s a few interesting learnings in there.

Adventure games are the genre that live and breathe story telling most, that seek to immerse the player into a different world – and it all stands and falls as to how well you immerse the player into it.

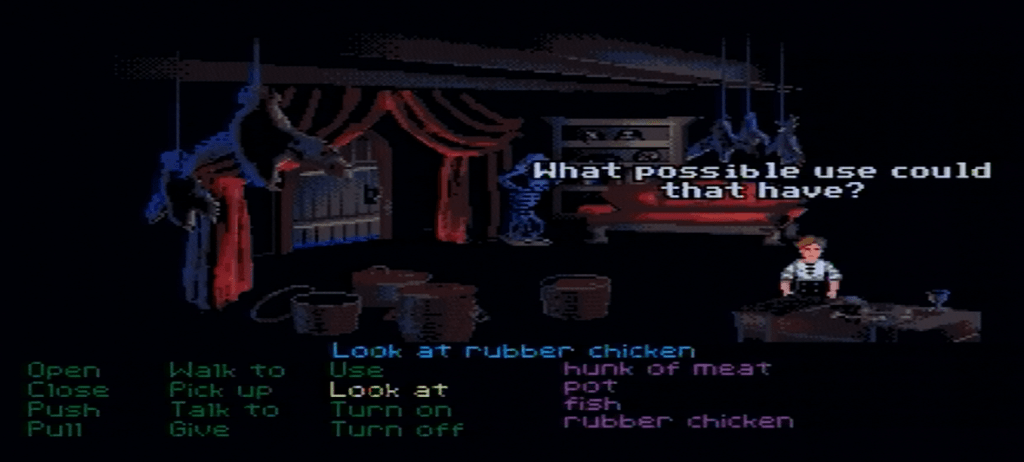

Ron Gilbert wrote his paper on “Why adventure games suck” in 1989 and republished it on his blog over here: Grumpy Gamer – Why Adventure Games Suck. He dove into how “suspension of disbelief” works for adventure games as well, and how important the user experience is, and how it can’t be disrupted by gameplay, complicated puzzles – and that the storytelling must be supported by puzzles, gameplay, dialog, etc. As early as 1989, he understood his product, the genre and the audience that play it well enough, to postulate a set of rules – most of which – as a player – I think hold true today. They also hold true to other areas of product management – you don’t have to be a game designer or a producer, to look for these qualities.

There’s a lot of truth in these rules, because they drive good, transparent and design for a user experience, lower frustration and allow for a user to interact with your system such that they can be successful without getting angry along the way.

- End objective must be clear: No matter if the persona you design or plan for is an end user or an administrator or someone specific, your experience or product should the clear on what and what not it will help them doing, what the boundaries are – so they understand where the user experience is headed.

- Sub-goals need to be obvious: give your audience an idea about what sub-steps they’ll need to take or you take them through, in order to complete their goal. If your product is setting something up for them, let them know how many steps and dependencies you will walk them through, and give them pointers as to how they connect to the larger goal.

- Live and learn: never create a situation where you fail and let the user stay stuck, making them restore an earlier snapshot of a configuration. There shouldn’t be learning-by-doing type situations that your feature allows happening that will result in the user restoring an earlier configuration in 100% of the time.

- I forgot to pick it up: Don’t assume that, if your feature has dependencies to other infrastructure being spun up or a configuration be done in a different place, that the user knows about it. Allow them to click a link that takes them to where the configuration happens, or let them do it in-line with your experience. If they need to stop your experience entirely, do something else, and come back (much later), that will cause frustration. Can some dependencies be solved later, after the user has gone through your experience? So you keep dependencies as asynchronous as possible?

- Give the player options: Don’t assume your users will configure or use your product in a linear order, when really there are no hard dependencies that require them to. Allow progressive setup and use of features and do not trap them, if a – seemingly unrelated – dependency isn’t there. You should not block them to print something on a printer, that wasn’t properly setup for sending and receiving fax.

There’s probably more, but this is all I can think of now. A lot of truth in that blog article, even though it’s been written a while back – and it was written for adventure games.