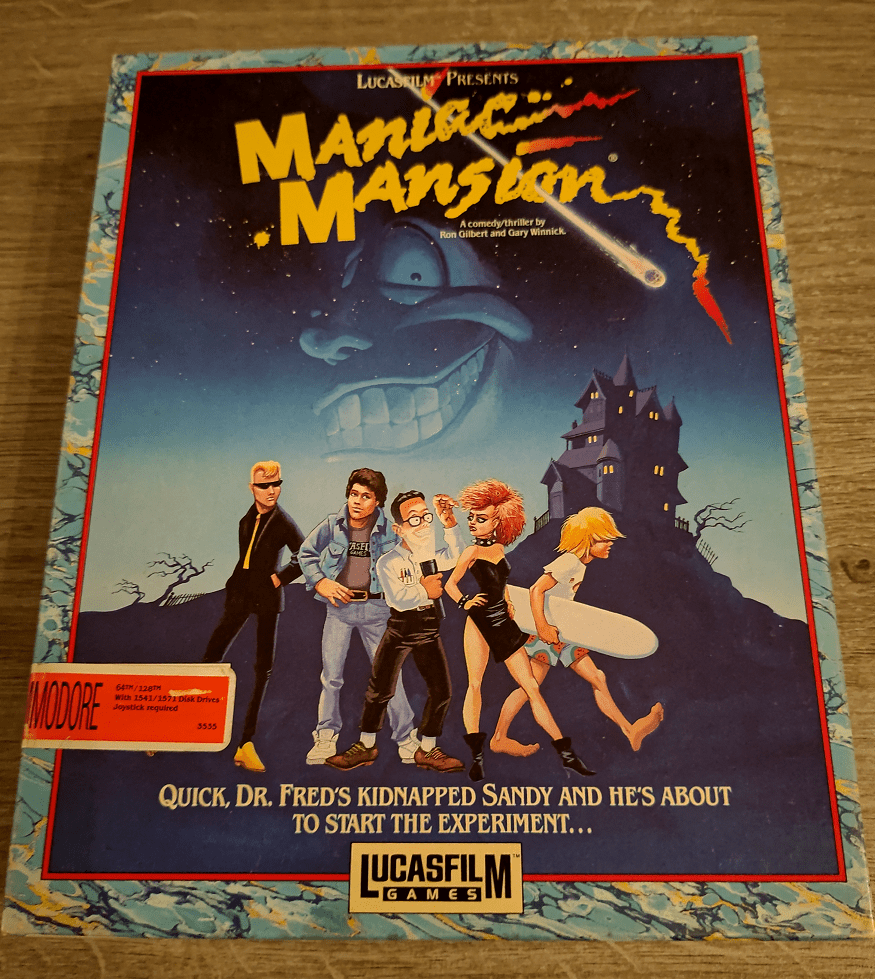

I am playing Maniac Mansion on my C64 at the moment. After I’ve successfully found and purchased it off of ebay, in a very good condition with all of its original big box, including its contents:

- Box

- Manual

- Poster of announcement board

- Response card for purchasing merch

- The 5.25″ disc – still working!

…I wanted to dive in, before I added the box to my collection. Playing for the first hours, it became apparent that I need to adjust to how the story of Maniac Mansion is told and how you progress through the story: there’s not too much guidance you get in terms of what’s expected to progress through the story – you need to figure it out on your own. You’re being given in the beginning, but nothing that structures your thinking and supports you progressing along the story.

That’s slightly different to how modern adventures treat this: newer adventures are very careful in giving you a helping hand and guiding you, especially in the beginning, through the learning process of what’s expected in this adventure and through the story, to set you up for success. That’s for a number of reasons: players simply don’t have too much time and patience to figure out a game any more. And a lot of the gaming platforms take returns if you played a game for less than a few hours – for steam, I think they’ll give you a full refund if you’re not happy when playing it under 2 hours.

Take Return to Monkey Island: you’re given a TODO list as a reminder of what you’re supposed to do, and if you haven’t played for a few days, when loading, you have the option of being reminded of what happened thus far in the story. This is a lot more engaging, and reminds you of the larger story you as the player are being part of, moving the characters and the story forward. It’s simply better story telling, as it keeps you focused and limits the “randomness” you might find yourself in, when you have no clue what to do next or where to go next.

Maniac Mansion is by no means a bad game – it’s set the bar for adventure games for years to come at the time, and brought a number of great concepts to the table – cutscenes for one, switching the characters and multi-character puzzles, as well as the different skills the characters had with the multiple possible endings. In hindsight, the cutscene could have been used more thoroughly to structure the story. They could have shown you the way to where Sandy is kept and then tell you what it takes to get her out. And build the story up from there. In a way, at times it feels like you’re wandering through the house, trying to solve puzzles and figure out where they take you next.

The cutscenes certainly help and drop a few hints – yet, it’s not like you’re guided through all of the story very tightly.

Clearly, over the years, the industry has redefined what storytelling in adventure games meant, and later games go great lengths in making sure the player stays engaged and the puzzles serve the purpose of moving the story along, rather than the puzzles exist and eventually, the game is over. The advancements in storytelling also help greatly in immersing the player in the game, making them spend more focused time with the game.

Here, I am surprised by the change and progression in story telling, immersing the player that happened between Maniac Mansion in 1987 and Loom in 1990.