I prepared an article for a German retro game magazine about the history of copy protection in games. It’s quite an interesting topic that I had learned more about in the past months, working on preservation of floppies, playing with my Kryoflux and looking into protection systems of the 80s and 90s.

I haven’t paid too much attention to copy protection during my youth, when I played on my Amiga 2000. A few games I bought my own (Christmas and birthday presents or money), other games I borrowed from my computer mentor when I was young – he lived next door with his family and got me fascinated with computers. He owned many games and would borrow me a lot of them.

Copy protection can be visible or invisible to you, as a gamer, depending on how it’s crafted and what priorities the respective publisher or studio had. There are a number of different types of copy protection systems that were used in the 80s and 90s – roughly categorized in “offline” vs. “online” copy protection.

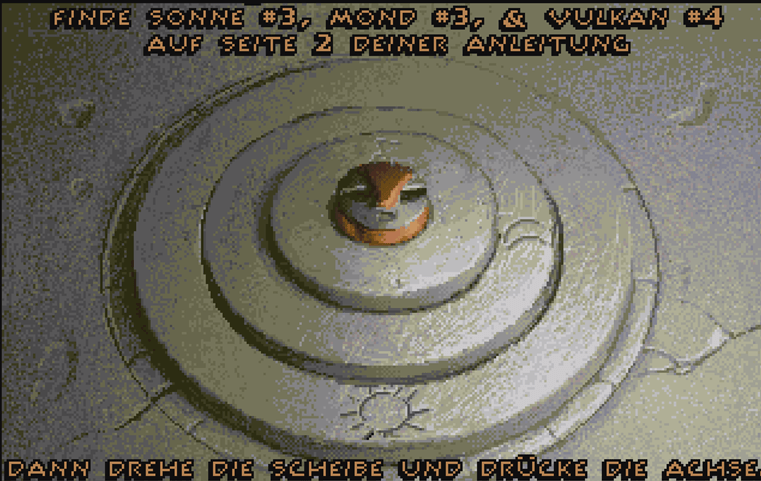

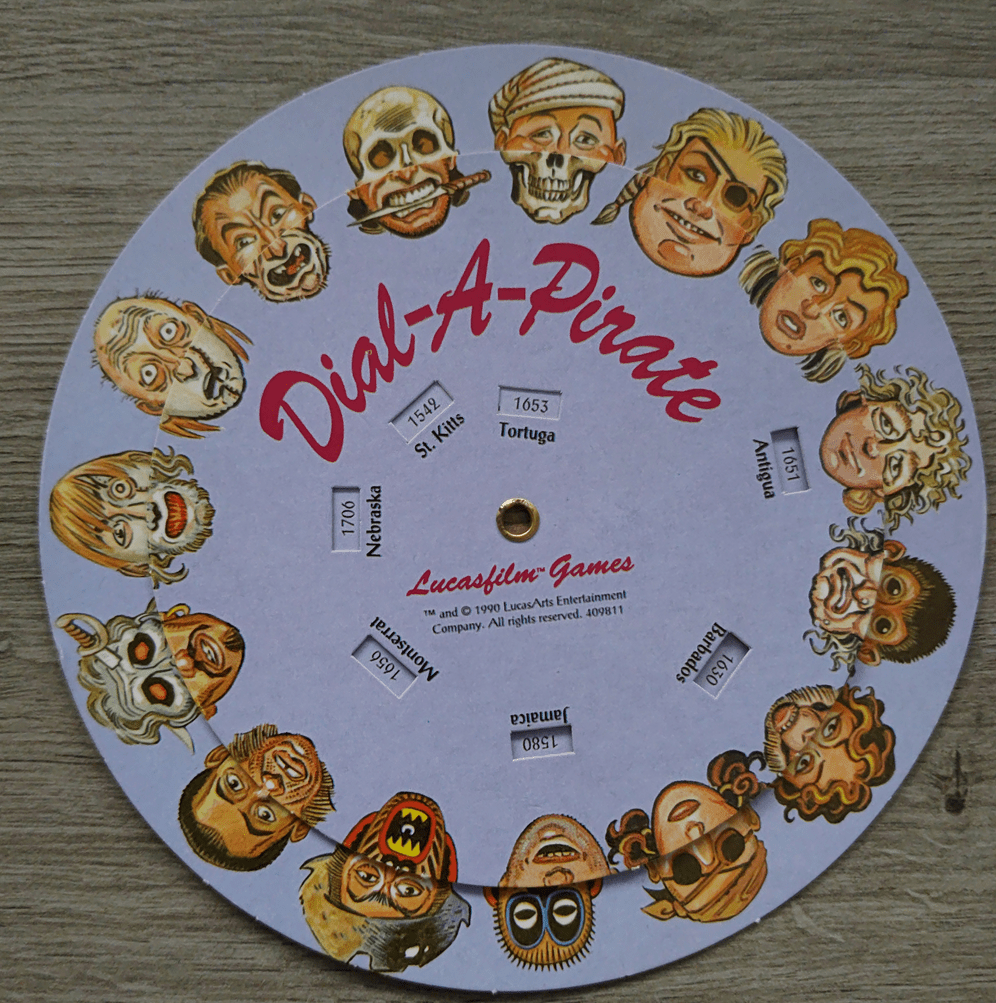

You may know offline copy protection very well: it’s the code wheels, the nuke ’em codes, the extra sheets of paper with information that come with your game box. The game would ask for a specific information to be entered either upon start, or during game play every so often. You’d then use the manual, code wheel or sheet, and transport the information over into the game again. If all checks out, you get to play – and copy protection is satisfied.

For Monkey Island, the game would display randomized top and bottom halves of pirates and ask when the pirate was hung in place X. You’d use the code wheel to replicate the pirate face halves and read 4 numbers where the place of death is – and that’s the code you’d use. For other games, such as Loom or Indiana Jones and the last crusade, you’d use a piece of red filter paper, to be able to read the codes you’d need to enter. At times, the codes aren’t just numbers or characters but also weird symbols that aren’t easy to explain. These codes needed to protect against two things: they should be hard to make a physical copy (difficult color choices, like black writing on brown background or very faint printing that can’t be picked up by a photo copier) and that the codes can’t easily be transported over the phone (weird symbols, hard-to-explain custom characters).

The Atari ST and Amiga game “Elite” had a very special copy protection scheme called “Lenslok”. The game would ship with a piece of plastic that contained two prisms that, when held against the monitor, would reveal information from otherwise unreadable lines and boxes that are displayed. It’s a strange concept and was also source for lots of frustration. So there’s a fine line to be taken here – how much do want to get in the way of playing, before you frustrate legitimate users? There could be an argument that, with “Elite”, if your chances of completing the check correctly with the Lenslok thing, are ~50% or less, wouldn’t it be more convenient to run a cracked version in the first place – and not be frustrated before even starting the game?

What’s also interesting: Apple thought about “security” mechanisms to protect their (and their partners’ and enemies’) software from duplication: the SSAFE project. Copy protection goes back to the late 70s and early 80s, and started out with interesting methods to “mess” with the physical media (datasette, floppy), such that a “home computer” floppy drive couldn’t copy the specialties directly.

The original floppies, created with professional hardware would be prepared with long sectors, long tracks, special “signal” patterns, that home computer floppy drives in the Atari, Apple II or Amiga could read, but not replicate when writing. These methods used near-hardware special tricks on the floppy medium to prevent copying. There were a number of methods that fall into that pattern.

Attacks from crackers didn’t really target the protection or the floppy layout itself, but could only work on attacking the protection checks in code, that would check for the long sector or long track and if it wasn’t there, panic because the copy is illegal. So crackers had to find and modify the code that checked for the protection. Sometimes that was easier, sometimes, it wasn’t.

In all known instances, copy protection was broken sooner or later. Is copy protection worthwhile pursuing and spending money on? Really it pushes the time illegal copies are circulated back by days, weeks, months, forcing eager players to getting a legal copy. The longer it takes, the more players can’t wait and buy. Will it last forever? Likely not, but copy protection did protect your revenue in the early days and weeks after you released your game. Assuming you were successful marketing your game with magazines and commercials early on, building momentum for the launch, that’s the most critical time for you to make money anyway.

Today, copy protection is still important. There’s a shift in mindset though – instead of just protecting software, platforms such as Steam try to bind the user on their platform and offering, next to the library and the copy protection, added value, together with the publishers – such as cloud backup of saved games, achievements, etc. The whole ecosystem is designed to give you added value, such that you want to buy the game from them — the copy protection just comes with it. That’s far better than “just” annoying the player with copy protection.

I think a few take aways for me are:

- Copy protection is as old as time – 1979 onwards _at least_. And it will stay for a while longer, I guess.

- Early copy protection mechanisms were wicked in the sense that developers really needed to know what’s going on with the hardware, and use that to their advantage.

- The schemes were mostly multi-layered – like specially prepared floppies, hidden copy protection check code, and code obfuscation with special CPU modes on the 68k CPUs.

- There’s a fine line between “effective” vs. “annoying” copy protection.

- Copy protection really is only there to increase the time it takes for a cracked version to be produced – it’s not there to prevent it. Days and weeks matter, if you’re releasing a new game.

- Trying to give the user/player additional reasons to buy the original, e.g. through platform cloud saves, additional goodies such as achievements that can be compared with other players, etc. — can they be pursuaded MORE to buy the original?