Designing your game for the right difficulty level is a challenge. We’ve all been at the point where we’ve played a game that was either too easy or too difficult. And especially in the beginning, when we don’t know what to expect from a game and when we haven’t grasped all the dynamics and mechanics just yet, we have the highest possibility of a drop-off rate. If I’m already overwhelmed or if I’m underwhelmed and I’m not necessarily interested in just a casual game, I may just drop off and not continue to play the game.

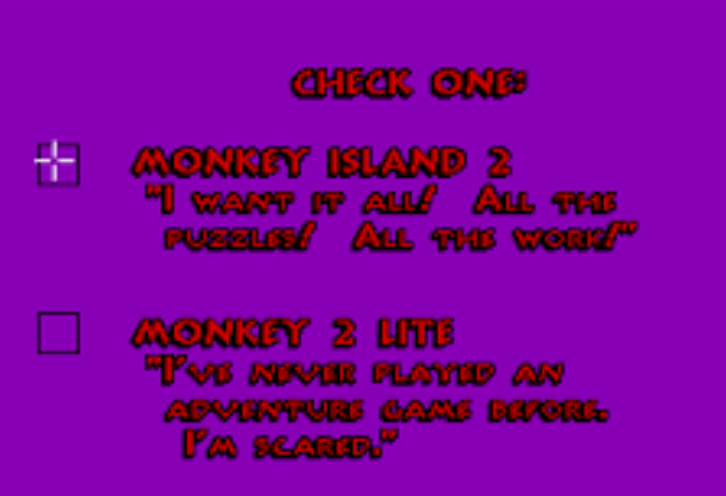

Additionally, getting the right difficulty in the beginning, throughout the game, and in the end game is hard. Usually, as a player, if you get to select a play mode and difficulty setting you want to start in, the settings aren’t very granular. It’s either difficulty sliders or knobs that let you define a global setting between easy, normal, difficult (, very difficult). They’re not fine-grained enough for people to find the right difficulty level. Worse yet, you often choose difficulty once, but can’t change it later in the game. Many difficulty levels can only be adjusted either before levels or only in the beginning on a new run. If I find that throughout a specific run, the difficulty is too high for me, I cannot just go and change the difficulty level back for a specific sequence or a specific end boss. No, I have to suffer through it. Another challenge is that the difficulty settings aren’t very declarative and aren’t very speaking of what I am getting.

What does “easy”, “normal” and “difficult” mean? We learn from experience that “normal” most often is the level that the designers have balanced the game the way it’s mean to be played in – but what does that mean, relative to my skill, and my previous experiences, so I can ease myself into the game? If anything, then there’s a small tooltip type answer that gives me an idea of how the developers would describe the levels they designed – but often, it’s not a real help for me to determine what my skill level matches to from a difficulty perspective.

If I’m a very seasoned ego shooter gamer, maybe I should be starting with hard or very hard even. If I’m new to adventures, maybe I should start with the softer variant that gives me fewer puzzles or the same puzzles, but a little bit more guidance. And I wished some of these difficulty controls that I’m getting throughout the games would give us a few more answers as to what each level that the developers cooked in, meant in their context, in their game, in their game world.

When designing difficulty levels, what usually happens within the game world is that we – as designers and developers – cater for two different things and adjust them. One is, that we cater for the user’s skill and how that skill progresses over time and how they get more proficient in or resourceful in approaching enemies, in jumping over cliffs, in understanding puzzles, in getting properly immersed into the game and thus be more successful and more straightforward in approaching specific levels, complexities and challenges. The other thing that we’re trying to cater for, is the resources that the game world gives the player and the resources that the enemies or the challenges have. One of the best examples for resource adjustment is that we give the player additional health potions or we give them a fire blossom, a fire flower to shoot, to make them more powerful, give them more options to heal – and make them more resilient. On the other hand, we may take away resources from enemies and give them less health points or we make them less persuasive when they chase the player, or we place fewer of them in the game world to bring down the complexity and the difficulty level that way. In a very, very difficult Doom level, the amount of ammunition that is distributed and the number of health packs that is scattered across the level, directly influences the difficulty of the level, because no matter how many enemies there exist, for as long as I can heal in between enemy encounters, I’ll be able to sustain more enemies and more combat and therefore bring down the complexity and the difficulty for the level for me.

The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild is taking an interesting approach when it comes to managing difficulty. In general there is only two difficulty levels that you can choose and they are stuck with throughout the whole game, and you cannot change the difficulty after you’ve started the new game. So it’s still a pretty significant decision to make when you start the game, considering that Breath of the Wild can easily take you 40, 50, over 100 hours, depending on what completion level you’re trying to achieve. You either choose the “normal” mode – or you specifically select “Master Mode” – which is an entirely different game experience.

The way the game approaches difficulty is by tracking progress the player makes – secretly keeping count on “points” that you collect along the way. You collect points mostly by taking on enemies in the game world and killing them. Harder enemies yield more points, easier enemies fewer. The game rewards the first 10 kills per enemy type with the points. As the points at up, for specific point milestones, enemies are upgraded throughout the world, changing some of them from the most basic health level to the next. If you encounter a group of 4 red Bokoblins in an area early on in the game – and you revisit the area later, 2 of these Bokoblins may have been upgraded to blue Bokoblins – the next level, that has more health points and potentially yields a weapon. Somewhat later in your game experience, you may visit the area again, the remaining red Bokoblins may be blue now, and the others may have upgraded to black or silver Bokoblins. Yiga Footsoldiers that you encounter, may become Yiga Blademasters. Red Lynel turn blue, later white, then silver. However, not all of the enemies of a specific group upgrade at the same time – the game is carrying only a portion of the enemies of a certain colour through the next upgrade.

So the game makes enemy encounters harder, as you progress through the game. This not only includes enemies in areas that you have already visited, but also new areas that you haven’t explored before. This is especially interesting, since BOTW is an open world game, so every run and every player’s experience, where they go first, after, when in the game they explore a specific area, may be different. The world level tries to ensure that, at least when you encounter enemies in a specific area, these enemies will be more challenging for you, relative to when/how you are there.

Zeldadungeon.net keep a list of levels and what upgrades are happening at World Level – Zelda Dungeon Wiki, a The Legend of Zelda wiki. The four divine beasts, the final monk from the DLC and Ganon (= the 6 “end bosses” of the game) yield the most points: 300, 500 and 800 respectively. Other enemies yield significantly less, but in line with general difficulty to beat. So it’s also fair to say that, when you progress through the main story and meet these bosses, you’ll also make a jump in your progression and difficulty level – indirectly through the enemy kills.

Next to enemies, there’s also a progression for weapons that you can collect and find throughout the world. Weapons and shields are becoming more durable and stronger, too.

This is a way of tracking user skill – by observing how many enemy encounters they’ve gone through and successfully fought enemies, the more experience they must have – and the more of the game they must have seen. However, counting killed enemies is somewhat flawed – I may have played 30 hours in the game world and only kill a few enemies, because I try and avoid conflict for quite some time, until I have enough shrines completed, which translate to heart containers and stamina – that make me stronger in the game world. I may actively avoid conflict and enemy encounters, until I have built up more resilience – and thereby outpowering the enemies that way. This was my tactic going through “Master Mode” in the first handful of game hours.

The game is also tracking “special skills”, too, as World Level – Zelda Dungeon Wiki, a The Legend of Zelda wiki describes:

During combat, if you manage to perform: a perfect guard, a critical hit or a perfect dodge, or you don’t take damage at all, you’re rewarded extra points, next to the enemy points – making you progress faster. These skills are special combos that you need to learn. They require some skill and patience to learn to time and execute correctly. Especially if you want to apply them reliably. Using these shows some player progress and proficiency – and when used consistently, is a sign for an advanced player.

Why is that world progression so important? Zelda is an open-world game and – after you’ve gone through the first 2-3 hours in the Great Plateau that could count as a tutorial type experience in the beginning, you’re free to roam the world and encounter enemies. These enemies, in their low-level form, clearly have the potential of killing Link easily – but these enemies need to be similarly scary later in the game, when you encounter them – possible for the first time – and you’re far stronger than when you were 3 hours into the game. Since it’s an open world, there is no telling when you meet a specific enemy or end boss in your journey. Even the four Divine Beasts and the bosses can be played in random order.

There’s potential for carrying this further – and have more of the game’s systems integrate more tightly to the actual progression that a player makes. One of the potential areas could be the weapons and the weapon exhaustion system. Ultimately, weapons break after a specific point in time when they’re used a number of times. We could envision a mechanism where, as the player progresses, would be more proficient in using and yielding a number of weapons, and that these weapons last a little bit longer.

There’s other areas in the game that don’t count at all into the progression system, and one of these could be shrines. Shrines give you the orbs that you convert into heart containers and stamina. If I am going and completing a number of shrines, couldn’t there also be specific milestones that trigger specific additional actions? For example, from the 120 shrines in Breath of the Wild, if I am completing the first quarter of the shrines, shouldn’t I be getting possibly another 500 world level points so that? The game world then could also level up with my progression. Even if I haven’t done anything else in the game world and I’ve actively avoided battling other enemies, I still made progress and I became stronger.

Another critique that I have is that the progression system isn’t really visible. The progression in terms of additional heart containers and stamina is very visible and a fantastic testament of how good user interaction and a user interface could be designed – especially in Tears of the Kingdom. However, the actual leveling in the world isn’t visible anywhere and I don’t necessarily mean that there needs to be a user interface – but I should more visually see the world change around me and that I can connect my progression with these changes. This could mean work the narrative into stories and dialog, that the hero is progressing, it could be changes in how the player interacts with the environment and that cutting a tree takes fewer strikes, or swimming is faster. Currently, if I know what to look for, then I can see the enemies change and some of the enemies in the enemy nests change too, but no one actually tells me that. Or I have no way of learning through in-game mechanisms that this is the progression system at play and that I am actually progressing – and therefore I am seeing more dangerous enemies than I fought before. Making the system more prominent could help motivate players and cheer them on, in this long adventure.

The last critique point is still: we’re missing a knob or control to fine-tune difficulty. I have no way as player to select my desired difficulty, or handicap. Since the world level system exists, maybe I would like to have the levels not to progress so fast, or I want them to progress faster, because I am a proficient player. If that control would exist, let me change that over time for me.

The other thing that I have would have wished for, but this goes down to game design and may or may not conflict a little bit with the open world design. I would have loved for some puzzles could be tied to my progression and the game world level that I am in at. For the most part, in Breath of the Wild, everything is accessible for you after you leave the Great Plateau. There is a number of side quests that are tied to other quests or other main story points that you have to go through for them to open up – or Divine Beasts/bosses to be beaten. But nothing really is explicitly tied to the game world level that opens up for you when you have a specific proficiency level. And we could imagine that there could be side quests there could be very dangerous – so dangerous that – story wise – you would only send the true hero on that journey. A journey that a NPC asks you to start for them that are tied to your level because they’re especially dangerous. Or you as the character have gotten the reputation of being the protector of the realm. And therefore they only approach you when you have gone through a progression that could have been helpful and could have been adding to the immersion and to the story arc.

All in all – I find the progression system in Breath of the wild fairly well designed. Towards the end, clearly you outpace the enemies in the world and you are proficient enough to beat them more easily. From a story perspective, that’s fine – you are supposed to be the true hero that saves the kingdom after all – so in the end, we want the story to end with Link as the hero. The progression system is fairly well designed, for what it is supposed to do.